Kandinsky’s Hissing Paintbox

“O please, gentlemen… that is a deep violet, please, depend on it! Not so rose!”– Franz Liszt conducting his orchestra in Weimar in 1842.

Like Bernstein, Beethoven and Rimsky-Korsakov, Liszt was a chromaesthete and experienced a rare form of synaesthesia (a kind of cross-wiring in the brain) in which certain sounds are involuntarily associated with specific colours.

It’s claimed that Beethoven saw the key of D Major as bright orange, while for Rimsky Korsakov, the key of B Major was a “sombre blue with a steel shine.” But although no two synaesthetes will necessarily experience the same colour and sound associations, Rimsky-Korsakov’s contemporary, Alexander Scriabin was so convinced that there was something deeper in the phenomenon that he developed his own musical system of colour, based on Newton’s Opticks and invented a colour organ which projected coloured light onto a screen while it was played. There was a strong spiritual dimension to Scriabin’s investigations and his unrealized master-work, Mysterium, was to have been a pioneering, multi-media extravaganza, set in the foothills of the Himalayas, in which music, scent, dance, and light would bring the entire world to a point of rapture.

And while Scriabin’s personal philosophy was driving him to break down the boundaries between music and art, Wassily Kandinsky was attempting to do exactly the same from the opposite direction.

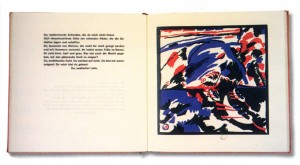

Three years before Scriabin died, Kandinsky published Klänge (Sounds), declaring that “Painting alone will not suffice.” The book, a collection of the artist’s woodcuts and phonetic poems, was supposed to break down the walls between the arts and “set the soul vibrating.” Whether or not Kandinsky actually saw sounds as colours is still a matter for debate, although he did claim to have heard his paintbox hiss when mixing colours as a child!

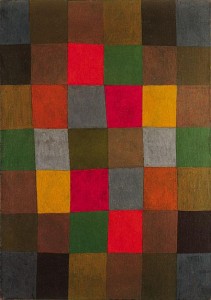

Kandinsky’s Blaue Reiter contemporary and Bauhaus colleague, Paul Klee, on the other hand, had a much more practical and pragmatic association with the world of sound. A classically-trained violinist of some skill, he eschewed a career on the concert platform in order to “be able to improvise freely on the keyboard of colours: the row of watercolours in my paintbox.”

Although music provided Klee with profound insights and a great many of his paintings include musical references in their titles (like New Harmony, pictured), Klee felt that what he called polyphonic painting was superior to music by virtue of its ability to transcend time.

On Seeing Things this month (my regular visual arts podcast for FromeFM on 96.6 FM) , I visit Hauser & Wirth Somerset and talk to composers Geoffery Poole, Julian Leeks and Jacob Vaughan-Churchyard Davies, about their attempts to turn the art of Zhang Enli (amongst others) into sound at a concert of new music commissioned by New Music In The South West, a Bristol-based non-profit that seeks to encourage, inform and inspire the region’s most promising young musicians. I also ask artists Debbie Locke and Fiona Robinson whether or not they felt any kinship with the sounds that their drawings inspired. And is Thursday purple or is it yellow, like Tuesday?

To listen to the programme, click here.

This Post Has 0 Comments